Dupuytren’s contracture (DC) is a progressive fibroproliferative disorder of the palmar fascia, characterized by nodules, cords, and eventual flexion contractures of the fingers. Its management presents persistent challenges—not only due to its progressive nature but also because of the variability in treatment outcomes and recurrence definitions. Recent research has aimed to clarify these issues, contributing to more standardized clinical care.

Dupuytren’s contracture is named after Baron Guillaume Dupuytren (1777–1835), a renowned French surgeon. He was the first to describe and surgically treat the condition in detail in 1831.

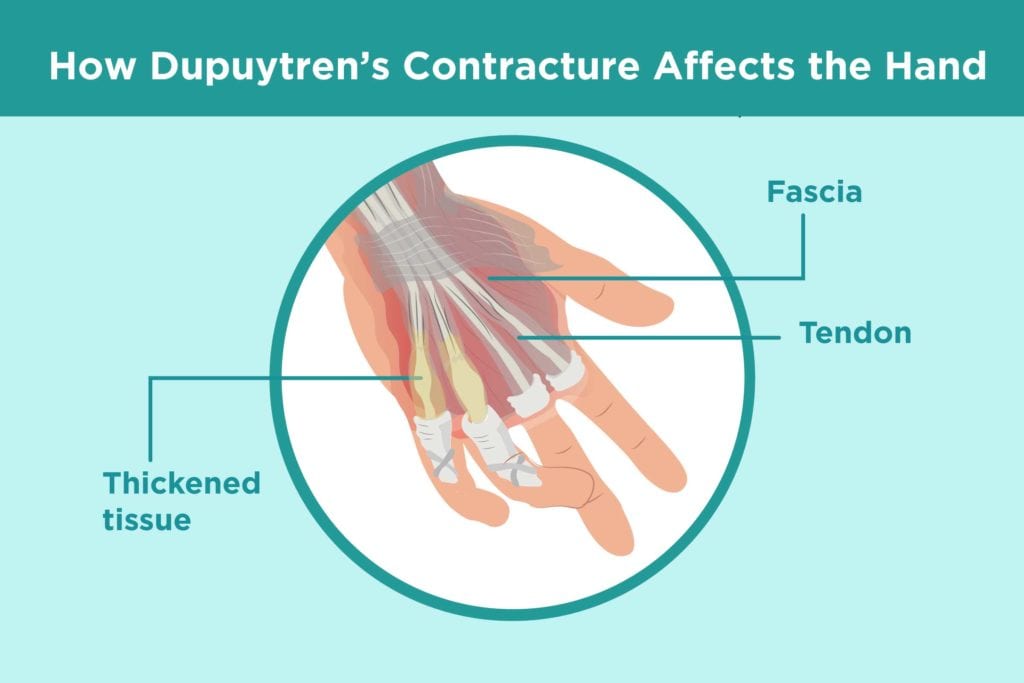

Figure 1 Trigger finger from Dupuytren’s (Rella, 2019)

Using the Delphi method, a structured communication process, an international panel of 21 experts from ten countries defined recurrence as:

“An increase in joint contracture in any treated joint of at least 20 degrees at one year post-treatment compared to six weeks post-treatment”

Key features of this definition include:

- Focus on angular measurement (contracture) rather than the presence of nodules or cords.

- Use of the six-week post-treatment measurement as a baseline, rather than intraoperative metrics.

- Emphasis on joint-specific recurrence rather than global recurrence across the hand.

- This provides a more objective and reproducible benchmark for comparing treatment modalities and enables clinicians to better understand long-term outcomes.

One of the most critical developments in the field has been the consensus-based definition of recurrence, presented by Kan et al. in PLOS ONE (2017). Historically, recurrence rates for DC have varied dramatically across studies—from as low as 0% to nearly 100%—due in large part to the lack of a unified definition.

A recent letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine critically examined the trial results from Dias et al., which compared collagenase injections with limited fasciectomy. The trial had concluded that collagenase was “not noninferior” to surgery, prompting debate.

In response, Blazar and Atroshi argued that:

- Collagenase injections showed superior short-term functional outcomes.

- Surgeons had more experience with surgery than with collagenase, possibly biasing results.

While recurrence rates were similar (17.2% for collagenase vs. 13.8% for surgery), reintervention was higher in the collagenase group—possibly due to differing thresholds for action, rather than actual treatment failure.

Moreover, the complication profile favored collagenase:

- Surgery carried risks including nerve damage (14.2%), infection, CRPS, and even amputation.

- In contrast, collagenase avoided many of these risks and required less downtime from work or daily activities.

The Importance of Accurate Diagnosis

Another key point raised by Rayan and Porembski is the potential misclassification of non-Dupuytren’s palmar fibromatosis as Dupuytren’s disease in clinical trials. Non-Dupuytren’s fibromatosis:

- Lacks genetic predisposition

- Is often non-progressive

- May not recur after treatment

Their concern is that inclusion of such patients may artificially skew trial outcomes, particularly recurrence and complication rates.

With a standardized recurrence definition and more comparative data on treatments, clinicians can now better tailor interventions to individual patient needs. However, challenges remain:

- There is still no objective biomarker or imaging standard to detect early recurrence.

- Long-term data comparing treatments beyond the 1-year mark is limited.

- Patient-reported outcomes, while valuable, are still underutilized in determining success.

As the field continues to evolve, studies like Kan et al.’s consensus on recurrence and the ongoing debates around collagenase efficacy and diagnosis accuracy reflect a broader move toward evidence-based, patient-centered care in Dupuytren’s disease. By aligning treatment goals, recurrence definitions, and patient expectations, we move closer to more consistent and meaningful outcomes.

References:

Blazar P, Atroshi I. Letter to the Editor. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(4):414–416. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2415164.

Bumbasirevic, M., Palibrk, T., Lesic, A. and Djurasic, L. (2011). Baron Gijom Dipitren, Guillaume Dupuytren (1777-1835). Acta chirurgica iugoslavica, 58(3), pp.15–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.2298/aci1103015b.

Kan, H.J., Verrijp, F.W., Hovius, S.E.R., van Nieuwenhoven, C.A. and Selles, R.W. (2017). Recurrence of Dupuytren’s contracture: A consensus-based definition. PLOS ONE, 12(5), p.e0164849. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164849.

Lurati, A.R. (2017). Dupuytren’s Contracture. Workplace Health & Safety, 65(3), pp.96–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079916680215.

Rella, M. (2019). Dupuytren’s Contracture: Treatment Options You Need to Know About. [online] CreakyJoints. Available at: https://creakyjoints.org/living-with-arthritis/treatment-and-care/medications/dupuytrens-contracture-treatment/ [Accessed 23 Jun. 2025].

Leave a Reply